Author

Format

1. Introduction

1.1 Introducing Re-Imagine Europe

Re-Imagine Europe (RIE) is an audience development, capacity building and transnational mobility programme funded by the Creative Europe programme of the European Commission (2017–2021). Re-Imagine Europe is a collaboration of ten arts organisations from across Europe, covering the fields of digital art, music, film and video: Paradiso (NL), Sonic Acts (NL), Elevate Festival (AT), Lighthouse (UK), INA GRM (FR), Student Centre Zagreb / Izlog Festival (HR), Bergen Kunsthall (NO), A4 (SK), SPEKTRUM | art science community (DE), and Ràdio Web MACBA (ES). Urban Paradoxes (NL) leads the audience development coordination and research. Collectively the Re-Imagine Europe partners embark on the process of making and producing art through new forms and new methods of cultural exchange. The programme produces, presents and distributes art, creates new audience development tools, provides new skills for artists and arts organisations and as a result, activates and engages the next generation of Europeans.

On the left: Lighthouse (UK): The Wave Epoch, Last Dance, May 2018. Photo: Elijah

On the right: Re-Imagne Europe website

With regard to audience development, the Re-Imagine Europe partners aim to deepen and diversify their audiences. Additionally, the partners and the artists and cultural entrepreneurs involved adopt radical approaches to audience development and aim to turn ‘audiences’ into ‘engaged citizens’, ‘active participants,’ and thus into ‘change-makers’. They do so by activating audiences to respond to the critical, social and political challenges, by facilitating exchange and dialogue, and by giving audiences the opportunity to develop their digital skills. As audiences, Re-Imagine Europe targets: ‘digital natives’ (16 – 35 years old) and ‘Europeans of tomorrow’ (6 – 16 years old). These new and diverse audiences will be actively connected to creative professionals and artists (‘multipliers’) and ‘European citizens’: a general culture-minded audience.

1.2 Introducing this article

A literature review was envisaged as one element of the research that is to be conducted in the context of the project. This article is one of the outcomes so far and several steps can be discerned in the process leading up to this article. In November 2017, Re-Imagine Europe kicked off with its first partner meeting. In the audience development session of this meeting, the partners shared their experiences and the aspects of audience development they were interested in improving. They expressed, among other things, the need for insights into digital tools to enhance audience communication and in how to extend relations with online audiences. Additionally, many aspects concerned the deepening of audience relations: ways to build longer-lasting relations and ways to develop new and active roles for audiences. While interested in exploring possible new relations with their audiences, at the same time some of the partners expressed the discrepancy they experience between their organisation’s take on audience development and that of policy and funding bodies they deal with in their respective countries. These partners expressed above all the need for an enhanced narrative on audience development.

And so the ‘double mission’ for the literature review was set: 1) what can we learn from the literature with regard to (digital) ways of deepening relations with audiences? and 2) How does the way in which audience development is approached in the literature relate to the practices of the project partners?

The next step was conducting the literature review for which roughly 100 articles were selected and reviewed: from policy documents and hands-on manuals to scholarly articles. The aspects the partners wished to gain further insights into functioned as guiding search terms to navigate and select from the vast body of literature on audience development. Additionally, interviews were conducted with the partners about their understanding of and rationale for audience development from the perspective of their respective organisations. Some interviews were conducted face-to-face at the partner meetings in May and October of 2018, others via Skype over the course of 2018. The final step was creating a meaningful dialogue in this article between the insights provided by the literature and the lived cultural practices of the Re-Imagine Europe partners.

2. The current take on audience development – the literature

2.1 The rationale for audience engagement and its effects

According to the European Commission, audience development brings cultural, social and economic benefits. The Commission’s perspective on audience development is built on three major assumptions as summed up by Kawashima (2000):

- The liberal humanist ideal of culture for all

- Barrier removal as the key to audience development

- Cultural participation contributing to the problem of social exclusion

These assumptions can also be traced in criteria set by funding bodies across the world. An 2014 Arts Queensland study shows that arts organisations applying for funding have to show, for example, how they understand and respond to audiences, the level of and plan for participation, how inclusive and accessible the programmes are for socially diverse audiences and communities, how much they invest in and innovate in arts education, participation and engagement, and how they demonstrate an understanding of effective community engagement processes. Although funding criteria may differ somewhat between national funding bodies, this study identifies four generic arts funding criteria can be discerned: artistic quality; audiences and proof of demand, reach and access; viability; and market development.

Lighthouse (UK): Re-imagined Futures, Last Dance, May 2018. Photo: Lighthouse

This also accounts for programmes such as the Creative Europe programme of which audience development is one of the priorities. The European Commission (EC) has identified ‘broader access to culture’ as a common priority for culture ministries across Europe, a priority thus further reinforced by the Creative Europe programme. Additionally, the EC (2012, p.4) sees audience development as a necessity because the world is rapidly changing: the digital shift, better educated populations, greater competition for leisure time, demographic change including declining and ageing audiences for some art forms, and the squeeze on public funding would pressure arts organisations to innovate and adapt. Framed this way, audience development becomes a matter of survival for (some) arts organisations and a matter of taking responsibility for wider (not primarily arts-related) political, social and even demographic changes.

Such funding criteria influence the direction and/or intention of the programmes developed by individual arts organisations – at least to some extent. It also influences the direction of research. In the review we found a large body of scholarly literature on understanding and lowering barriers to participation and on the development of forms of active audience involvement. Walmsley and Frank (2011, p.9) maintain, for instance, that arts organisations should empathise with the barriers audiences face in engaging with their cultural events as well as appreciating what motivates them to attend. For a sustainable audience development it would be equally important to understand who is not your audience, and why they are not attending. In the consulted literature, frequently discerned obstacles are physical and financial barriers to arts participation, as well as the social barrier, which would be hardest to tackle. On the one hand, social aspects function as a motivation for arts attendance: socialising with friends or family members was the most common motivation for arts attendance in a 2015 NEA report on audience participation. On the other hand, social aspects become barriers, according to OMC (2012, p.55), when (potential) audiences feel that the cultural events would not be ‘for the likes of them’. Creating appropriate social opportunities is, therefore, as several scholars (e.g., Brown 2013) maintain, a critical aspect of building participation. Arts organisations should create an open and welcoming atmosphere. A social invitation would be powerful enough to circumvent all sorts of barriers. And communication is seen as key to overcoming social barriers: the audience needs to understand the ‘language’ of the organisation and the ‘codes’ of cultural participation. A programme that tapped into this line of reasoning is ‘Not for the likes of you’ of the Arts Council of England. Another important barrier to arts participation, often discussed in the literature, is lack of time.

In the review we also found a large body of literature addressing the third assumption: understanding the relation between arts attendance and social inclusion. Bollo et al. (2017) speak of ‘audience by surprise’ in this context, referring to people who do not participate in any cultural activity for a complex set of reasons related to exclusion, education and accessibility. Their participation would hardly materialise without an intentional, long-term and targeted approach by arts organisations. The OMC report (2012) offers examples of art institutions that work on such an approach in partnership with sectors such as healthcare and social care. Or as Cogman (2013, p.8) puts it in her audience development toolkit, social inclusion initiatives by arts organisations can focus on national or regional governmental priorities, targeting specific hard-to-reach groups with the aim of benefiting these groups and society as a whole. Such a social perspective is also dominant in the long history of literature on extra-curricular art education, community art and/or outreach programmes set up by arts organisations that are seen to contribute to things like social cohesion, active citizenship or community empowerment (e.g., Stern and Seifert 2013; Webster and Buglass 2005; McCarthy et al. 2004; Lowe 2000; Landry et al. 1996). The effects and impact of such programmes on the arts and/or the arts organisation are mostly not discussed in the literature.

2.2 The three dimensions of and two approaches to audience development

If the literature review shows us one thing, it is that there is no universal, clear definition of audience development. What can be discerned are different dimensions in audience development: 1) increasing or developing audiences; 2) diversifying audiences; and 3) deepening relationships with existing audiences (European Commission 2012, p.3). Audience development is seen in the consulted literature as sustainable when these three dimensions are combined, but what follows from the literature is a plethora of strategies with regard to these dimensions. This is true for strategies identified by different scholars, or within one and the same source. Kawashima (2000) developed, for instance, four distinctive elements in relation to the dimensions of audience development: cultural inclusion, extended marketing, taste cultivation and audience education. The organisation’s policy aims would determine which element should be central in their approach. If an organisation primarily wants to target non-attenders, it should focus on cultural inclusion and extended marketing. In the event that the organisation wants to target existing audiences, it would need to engage in taste cultivation and audience education. Furthermore, the literature review shows that many arts organisations develop only a partial strategy to audience development as they concentrate on finding new audiences. According to Hayes and Slater (2002), this often results in short-term projects targeting minority groups, while the potential offered by existing audiences is being ignored. In this narrow approach, audience development can be understood as merely a marketing strategy to increase numbers at short notice by aiming at easy-to-reach audiences.

Also apparent from the literature review is that there are two distinct approaches to audience development: 1) a marketing-oriented approach, and 2) a holistic approach. The marketing-oriented approach to audience development is aimed at new audiences and is focused on art attendance. The goal of this approach is to increase the number of people attending. Both ‘building audiences’ and ‘diversifying audiences’ can be dimensions of this approach, but the role of the audience remains passive. In the holistic view on audience development, the audience is involved through audience engagement. Audience development is seen as holistic: that is, as a continually, actively managed process in which the entire arts organisation is involved. It includes aspects of marketing, commissioning, programming, education, customer care and distribution.

The consulted literature indicates that, over the years, the holistic approach has become more dominant in both literature and practice. Moreover, audience development is now understood as a deliberate, strategic process of creating meaningful, long-term connections between people and the arts organisation (e.g., Bollo et al. 2017; Cogman, 2013). The audience’s role is active, can take on different forms, and the engagement can occur in all stages of what the European Commission (2012, p.5-7) called the artistic value chain: upstream in the organisation’s creation, programming and production processes, midstream in the artistic process, and downstream in participatory activities with the artistic work. Through such engagement, arts organisations can build, diversify and deepen relationships with the audience.

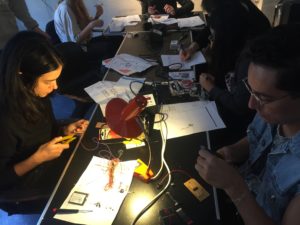

A4 (SK): Workshop And then the silence smiled with Kateřina Zochová, May 2018. Photo: A4

2.3 Creating audience engagement

The current take on audience development is therefore that it should focus on a two-way exchange between the organisation and the audience. Following the dominance of the notion of engagement in the current take on audience development, many scholars analysed various engagement programmes and/or specific forms of engagement. Brown and Ratzkin (2011), for example, found four categories of engagement programmes while assessing the efforts by non-profit arts organisations to engage audiences: 1) engagement via technology; 2) collaborations and partnerships across disciplines and sectors, to overcome barriers to implementing more engagement activities and to integrate art into civic dialogue; 3) experimentation with setting and venues; and 4) participatory engagement, involving some form of physical or creative expression by the audiences. We briefly explore the first and fourth category, following the interests of the Re-Imagine Europe partners.

Engagement via technology

The consulted literature indicates that participation can take place online and offline. For instance, the interplay of arts education and digital media is seen by several scholars as a way to engage especially a young audience (e.g., Brown, 2013; Lin & Bruce, 2014). A returning aspect in the literature on digital approaches of arts organisations is the notion of the ‘active’ audience. Walmsley (2016) suggests, for instance, that Web-usage should be more interactive with better tools for creative expression such as responsive digital platforms. These platforms would democratise critical exchange and foster more reflective critique. However, among others, O’Sullivan (2010) ‘warned’ that arts organisations should be aware that different audiences want different things from sometimes very similar technologies and that the vast majority of digital platform users is not actively posting but only reading. Vlieghe et al. (2016) too consider it crucial that arts organisations support the interests of its audience by allowing various digital engagement possibilities, but point out that organisations should also acknowledge the rationales for having audiences participate in online platforms or social media, such as sharing experiences, meeting enthusiasts, creating identity, and acknowledging and encouraging participation (among users and staff).

Thus, one the one hand, scholars identify chances for digital engagement, as it would facilitate contextualisation and cognitive decoding of the art context, and democratise critical exchange. This in turn would positively shift perceptions of art forms unfamiliar to the (non)attenders, increase audience anticipation, and enrich their engagement during live performances. As such it could also be an instrument in breaking down barriers to attendance. On the other hand, studies point out the limited use of digital engagement to date. Although the digital sphere could offer arts organisations various modes of audience engagement, currently, as a study by King’s College London (Ellison 2015, p.16) pointed out, organisations apparently use digital media merely as “a means of capturing, recording and storing work, creating online, educational resources or marketing”. They also use social media channels for distribution and marketing. But, according to the report, the purpose of the digital media usage, so far, is seldom ‘digital’ or ‘creative’ in itself. One of the interviewees, cited in the report (Ellison 2015, p.16), maintains that “a more rounded sense of the value proposition for social media and digital in the life of national, regional and local arts organisations clearly needs to emerge, and does not seem to be doing so organically from within the sector’s own partnership activities”. A report by Nesta (2015) points out that the limited use of digital technology is due to a lack of expertise, inadequate IT systems and the absence of senior digital managers and coherent organisational digital plans in arts organisations. Some organisations find their digital projects too resource-intensive and refrain from developing them. In addition to capacity building, Nesta identifies partnerships as key to enhancing the use of digital technology.

Consequently, many articles conclude what arts organisations could or ought to do in the digital sphere. We did not find any practical guidelines or manuals, and the literature review offered just one example of a creative application of digital means. This concerns the case of Paradise Laboratories, an experimental performance company that explores the use of the Web to create original online participatory theatre programmes. The organisation’s online performance platform contains different formats to activate audiences by enabling co-creation in offline/online performances. The online programmes can be designed to interact with offline ‘real’ theatre events or to result in independent Web-based art works. An example of a collaborative Web performance that happened both on- and offline is ‘Fatebook’. In this collaboration of artists and audiences, thirteen people created fictional identities on Fatebook. The audience first encountered these identities by ‘friending’ with the characters on Fatebook’s social media platform, where they built an ever-expanding theatricalised online community. Finally, during a 70-minute real-time performance, the thirteen characters interacted with scenes projected on screens, the audience, and one another. Audience members curated their own theatrical experience by choosing when and where to watch content and which of the characters to follow and engage with.

Participatory engagement

Brown and Ratzkin (2011) call the increasing availability of interactive and participatory activities in different stages of the artistic value chain ‘a trend’ in audience engagement programming. The consulted literature also expresses a strong belief that barriers to attendance can be removed through genuine, active participation. The three terms frequently encountered in the literature in this context are: engagement, participation and community building. Stallings and Maudlin (2016, p.6) point out that the terms engagement and participation are often interchanged and are also widely used beyond the art sector: “Public participation is a concept based on the belief that those who are affected by a decision have a right to be involved in the decision-making process.” Stallings and Maudlin continue stating that some scholars define arts participation as a measure of arts engagement, where engagement is synonymous with involvement, but other scholars consider arts engagement a process and a correlate of community engagement. They quote Borwick for whom it is a “mission strategy of building deep relationships between the arts and their communities for the purpose of achieving mutual benefit, in which the arts and community are equal partners” (Borwick 2015 in Stallings & Maudlin 2016, p.6). Here the concept of community engagement overlaps that of community building, because, according to Borwick (2012), both approaches take relationships as the key commodity and emphasise the establishment and maintenance of long-lasting relations. Audience engagement and community building concern both existing and new audiences and can thus simultaneously trigger the deepening relations with and the diversification of audiences.

SPEKTRUM (DE): Workshop Sonic Vibration – Materiality of sound with Andrey Smirnov, September 2018. Photos: SPEKTRUM

Whatever the terminology scholars apply, the consensus is that in order to foster long-term cultural participation among non-audiences, the role of the audience should transformed from being ‘passive spectators’ to ‘active participants’. For example, Walmsley & Franks (2011, p.12) found that successful arts organisations embrace the opportunity to work with their audiences on many organisational levels by offering various different forms of engagement. Two key elements in this process of establishing relations that we found in the consulted literature are identification and mutual trust. To enable identification, arts organisations need to offer the audience a voice, enable different forms of participation, and customise the communication. That is to say, by gaining a voice, the audience is thought to feel more connected to the organisation. A relationship extends a person’s identity by enabling him or her to belong to the organisation and the community around it. Besides a ‘sense of belonging’, this community can offer people the opportunity to share their experiences and thoughts with others, which makes it again more meaningful. Conner (2013) analysed, for instance, an increasing importance of learning-communities, where audiences can control their own interpretations and have pleasurable (social) experiences. When the audience identifies with the organisation and its community, their loyalty increases and this is desirable for the organisation’s sustainability. Secondly, mutual trust is considered vital to building long-term relations. The consulted literature maintains that mutual trust would increase when the input of the audience is seen to have its effect on the arts organisation.

The other two types of engagement programmes, mentioned above, can reinforce identification and mutual trust. One way towards a new audience, mentioned in the consulted literature, can be the creation of innovative experiences for non-audiences outside the walls of cultural institutions, in public space or (non) arts venues in the community. Another way arts organisations can gain the trust of the non-audience is through partnering with other organisations (inside and outside the culture sector) with which the non-audience is already familiar. The consulted literature indeed stresses the importance of building communities, or networks, with partner organisations. Long-term partnerships bring a continuous exchange of knowledge, ideas and skills, but they are also beneficial for the audience development, as audiences can be shared and exchanged among the partner organisations.

Whilst identifying positive development and chances, scholars simultaneously point out that a strong focus on and awareness of the preferences of the audience is a necessary condition for nurturing identification. In this context, for instance, Brown and Ratzkin (2011) maintain that arts organisations need to consider the different engagement preferences of their audiences. For this purpose, they determined six different audience typologies: Readers, Critical Reviewers, Casual Talkers, Technology-based Processors, Insight Seekers, and Active Learners. In order to engage people representing these typologies, Brown and Ratzkin (2011, p.8) state that arts organisations may want to provide a diverse menu of programmes and activities — social and solitary, active and passive, peer-based and expert-led, community-based and audience-focused. This would help to increase the experience and uptake of the artwork by the different groups with their disparate preferences for engagement. Brown and Ratzkin found, however, that most arts organisations are particularly adept at serving Readers (who like to read a bit of information beforehand) and Insight Seekers (those intellectually curious joining lectures and discussions). According to them (2011, p.34), the challenge arts organisations face is to figure out how to serve the other segments ‘small bites of context and insight’.

2.4 Many possible active roles for audiences

With regard to the creation of audience engagement and building long-lasting relations, we discerned in the consulted literature – particularly in articles on specific case studies – a range of active offline and online roles for audience members to engage in. Three types of participation stand out: 1) participation of audiences in and around artistic products or processes; 2) participation of audiences at the organisational level; and 3) participation of audiences through memberships or financial relations. We briefly discuss some examples of these strands below.

First, there is the range of forms of audience participation in and around artistic products or processes. The aim of such programmes is, according to Lipps (2015), to build community ownership, participation and a relationship with, and support for the organisation, its programme and its people. In addition to audience engagement, quality visitor experiences would be key to achieving this. One established and widely accepted form is participation in educational activities. This mainly concerns activities additional to the artistic core product to deepen the experience of the audience and to reach out to other, often young, audiences. Think, for instance, of workshops or interactive pre- or after-talks that almost all cultural institutions have in place. Another form of this type of participation is through interactive elements in the performance or exhibition. Certain theatre forms entertain this type of interaction as the core of their theatre practice. Examples are forum theatre and immersive theatre plays in which the audience can intervene or take active part in the story and theatrical action. This type of participation can also take place in an exhibition in which audience members find their own routes to create their own individual experience of the work. In terms of sustainability of the relation built with the audience, OMC (2014, p.95) advocates ‘duration in time’, because: “Projects aiming at participation in the arts may have an empowering, and sometimes even healing, effect. However, letting people down because the project has ended may produce the opposite result, and produce disappointment and loss of trust.”

Several scholars take it up a notch and consider the artistic experience, stemming from a high level of audience involvement in the art process, as the core customer value. For instance, Boorsma (2006) argues that audiences should be seen as co-producers in the total art process, with the artistic experience as the reward for the co-creative efforts of the audience. According to a report on audience development and the Creative Europe programme (2012), co-creation and user-led or user-generated content facilitated by digital technologies would be a global trend. Moreover, this report expresses the belief that the future of audience development might lie in even greater levels of interactivity in the creation and production processes. In co-creation or co-production, rather than participating in a preconceived artistic product, the audience is able to co-shape, influence or change the artistic outcome of an art process. Co-creation requires a profound level of interaction between audience and artist. Walmsley (2013, p.2) points out that successful co-creation involves trust, respect, collaboration, exchange and playfulness. Co-creation attracts a highly niche audience of active learners and risk takers, therefore Walmsley (2013, p.10) maintains that organisations striving to increase loyalty through this type of active participation, must be aware that they might alienate people who are happy to leave the production of art to artists.

Second, there is a range of forms of audience participation at the organisational level. These vary from more detached to highly engaged forms. A light version of this type of participation is in audience consultation processes, for instance, in audience research (surveys, interviews, focus groups, etc.) aimed at gathering information on the audiences’ experience. From the literature we learn that arts organisations presently have only limited, if at all, insight in the different roles their audiences pass through. On a similar note, the literature suggests that arts organisations should shift their focus from obtaining quantitative data (surveys) to qualitative research on why audiences attend or participate and what they take away from this. Alternative measurement systems must be developed to measure the impact of participatory strategies. Foreman-Wernet and Dervin (2017), for instance, suggest the ‘Sense Making Methodology’ that maps different views of the artistic product and the organisation held by audiences and professionals. The methodology analyses patterns of audience actions and attitudes over time.

A more active form of participation is in panels or stakeholder meetings with representatives of audience segments the arts organisation likes to reach. These (curatorial) panels offer, for example, programming suggestions and/or reflect on draft versions of the programme. This is seen as a means to diversify audiences. Arts organisations can also stimulate diversification through ambassador programmes, a current trend in building networks in the arts. One example is the ‘EXPOSED-team’ of Eye Filmmuseum, Amsterdam. The team of one community manager and six young members provides in its own way context for the EYE programme, via an online magazine and by organising its own (side) events. The team is also asked for feedback, for example, on future programmes by Eye. Another example is Deventer Schouwburg (NL), which invites people from the city of Deventer to become ‘fan’ of a theatre group, e.g., Toneelgroep Oostpool. They gain a voice in decision-making, and as ambassadors they both ‘consume’ and promote a play. More radical forms of involving people at the organisational level are temporary ‘take-overs’. One example here is the TakeOver Festival from York Theatre Royal (UK). For three weeks the theatre’s management stands aside and hands over complete responsibility for the programming and running of the theatre to a group of under 26 year olds. The theatre staff fulfils only a supporting role. Another example is Showroom MAMA’s Summer Swap in 2017, which this Rotterdam based gallery announced as: ‘MAMA goes on holiday. Concrete Blossom and Damage Playground are taking over. What are their plans? We don’t know. But they have our trust.’

Another active supporting role is volunteering – in real life or virtual (e.g., Cravens 2000). Volunteer programmes are sometimes born out of economic necessity, for instance, as strategies to generate alternative forms of income and resources to supplement art grants (Bussell & Forbes 2007). But other ‘motives’ and benefits are mentioned too. For one, it is seen as a way to improve the link to diverse audiences (Davies & Wilkinson, 2011). Other benefits mentioned are: volunteering in the overall operation of the arts organisation will give the people concerned an ‘insider’ feeling; free access to the event; and it will provide an impulse to their professional and personal development, such as, e.g., presentation or project management skills (cf. Hotdocs, 2015, p.39-40; Arnett et al. 2003). In that sense, some scholars emphasise the mutual benefit – Rentscher et al. (2002) speak of ‘the exchange of value’. Manuals exist supporting the arts organisations in setting up volunteer programmes and offering guidelines for volunteer management (e.g., Hotdocs, 2015; Stamer et al. 2008). There are arts organisations that work with volunteers on a structural basis. For example, volunteers are an important aspect for the nine galleries and museums of Tyrne and Wear Archives and Museums (TWAM). On the ‘TWAM volunteering’ website new volunteering challenges are uploaded all the time, making it easier for volunteers to get involved. The challenges differ in focus and duration. Some can be completed in, for instance, one minute (such as sharing a photo on social media, posting a tweet or sharing a suggestion), in one or two days of volunteering (e.g., as an assistant or a fundraising volunteer during an event), or in weekly or monthly volunteer roles (e.g., digitising the collection, working as a gardener in the community garden or as a catering assistant).

Some arts organisations developed participatory decision-making processes as the fundamental, structural basis of how an organisation is run. In this respect, Jancovich (2015, p.1) points out that much of the literature shares the assumption that the deficit (in participation in the arts) lies with the non-participant, in terms of either understanding or opportunities to engage. Strategies to increase participation therefore commonly focus on education programmes or concessionary pricing. Jancovich sees most art institutions trying to increase participation in their existing activities rather than being willing to change the way they operate. At the other hand, Jancovich finds at least some scholars who argue that the deficit may be in the management of the organisation, or the cultural offering, as much as with the recipient. In her article, Jancovich therefore explores what the implications are of moving beyond the deficit approach to participation, to a process whereby consumers are involved in shaping how arts organisations are managed and programmed. Looking at processes of participatory decision-making, whereby organisations interact with their users on the planning and delivery of services, where such processes have been implemented she finds a resistance to the concept of participatory decision-making in the arts sector as well as demonstrations of powerful outcomes, in terms of both artistic and audience development (2015, p.2). Jancovich provides the example of Contact Theatre, Manchester. An example we came across at the Art & Audiences Conference, in Gothenburg in 2017, is Science Gallery Dublin that has put public participation at the heart of its organisation. Engagement is facilitated at every step of the way: from a (global) open call for exhibition themes, to the ‘Idea Funnel’ in which the choice of themes is structured, to the connection made between professionals, upcoming artists and amateurs in the research projects that result in the exhibitions, and the mediation during the exhibitions. The exhibitions do not mark an end point, but are ‘works in progress’ as the audience develops and changes the work with the artists and designers. The organisation has become porous, allowing ideas to come in from the outside. The Gallery understands itself as a cultural incubator and does not hold itself responsible for how things are developed.

A third strand is audience participation through memberships or financial relations. One such relation is facilitated through membership programmes. This can concern memberships or friends programmes related to a specific arts organisation, as well as to a consortium of such organisations. An example is the cultural membership organisation ‘We Are Public’ (NL). The organisation’s editorial staff selects the best concerts, performances, films and expositions from the programmes of the We Are Public partners in the respective city. For a monthly fee, members have access to a selection of 50+ cultural events a month. The selection cuts across disciplines, contains mainstream, niche and alternative events. This way, the scheme reaches a new and larger audience for the cultural partners involved – meaning both audience development and an increase in ticket sales.

Another – double – incentive comes from crowdfunding. Besides financial support, crowdfunding enables the organisation to involve audiences in realising events, which may give them a sense of co-ownership. A successful Dutch crowdfunding platform for the creative sector is ‘Voor de Kunst’. However, crowdfunding is a demanding process and external expertise and partnerships are often a requirement for its success. From their study of the European cultural and creative sector, De Voldere and Zeqo (2017) conclude that the adoption of crowdfunding is still in an early stage and that to date success rates remain low. To be successful, crowdfunding demands consistency, e.g., an annual crowdfunding campaign can offer a fixed moment of contact and collaboration with the audience. The international frontrunner in ‘serial’ crowdfunding is the Louvre Museum. Every year since 2010, the Louvre has held a campaign to acquire a new artwork or to begin a restoration project. Research has shown that over 50 per cent of the people who donated took part in other crowdfunding campaigns in subsequent years (De Voldere & Zeqo, 2017). The ‘reward’ for the donors varies from a free ticket or a behind the scenes experience, for example, to a piece of art. Crowdfunding is a structural part of the Louvre’s marketing strategy as it builds sustainable and loyal relationships with the audience.

2.5 Implications of audience engagement for arts organisations

Several of the studies on a sustainable audience development in our literature review point out that effectively achieving audience engagement demands certain attitudes and actions on the part of arts organisations. For instance, Maitland and Meddick (2000) define audience development as a planned process, which involves building a relationship between an individual and the arts. This takes time and cannot happen by itself. Arts organisations must therefore work on developing these relationships. Or rather, a sustainable audience development would require the entire organisation to be involved. In addition to such a holistic approach, other (interrelated) implications for arts organisations we found in the literature are: sharing power, strong leadership and partnerships. These are discussed briefly below.

A holistic approach

According to Sidford and Hinand (2014), the success of audience engagement is dependent on a wholehearted and institution-wide commitment, and this commitment must be evident in all aspects of the organisation’s operations. Many scholars agree that marketing, education and programming are the most obvious departments involved in audience development, but maintain that audience engagement is to be integrated in all work departments (e.g., Brown & Ratzkin, 2011; Fiaccarini et al., 2016; European Commission, 2012).

An area that needs action, according to Bamford and Wimmer (2012) in a report written in the run-up to the Creative Europe Programme, is the organisation-wide definition of structures and responsibilities regarding audience development. In the current state of audience development another field that needs action is capacity building with regard to audience development (Bamford and Wimmer (2012); Bollo et al. 2017). This is seen as key to the staff committing fully and to bringing audience development into the core of the organisation. Capacity building should be directed at office staff as well as at artists working directly with audiences. As we saw above, a specific area that requires capacity building is the use of the digital sphere in audience development.

Bergen Kunsthall (NO): Who’s doing the washing up where is the sink? by Aliyah Hussain and Anna Bunting Branch, August 2018. Photo: Thor Brødreskift

Additionally, Cogman (2013) maintains that in the holistic approach, arts organisations should engage external expertise by appointing an audience development manager and/or by collaborating with partners. In choices for partnerships, external artists and locations, arts organisations ought to aim for diversification. This is in line with one of the conclusions the European Commission drew from the ‘European Audiences’ conference (2012): the holistic approach to audience engagement needs to be reflected in the organisation’s internal structure and in the diversity of its workforce and partners.

Leadership

Furthermore, the literature review showed that changing an organisational culture and bringing audience engagement into the organisational core demands confident leadership. Good leaders recruit and select a diverse staff and do not try to lead the change alone. Rather than directing change, Fiaccarini et al. (2016) maintain, cultural leaders provide a climate in which change can occur: leaders have to assume the role of ‘change maker’. Jancovich (2015, p.9) argues that the ethos of arts management needs to shift to a ‘relational leadership model’ that nurtures a shared vision across the organisation, in particular if arts organisations decide to implement participatory decision-making. Jancovich (2015, p.10) adds that space should be made for dissenting voices to be heard, to avoid the tendency towards path dependency in organisations, and, instead, offer transparency in how the internal decisions are informed by such processes.

Sharing of power

Audience engagement additionally implies the sharing of power between the arts organisation, the artists involved and the audiences, for instance in co-creation or participatory decision-making (with a select few). Jancovich (2015) states that this is most effective when people genuinely want to change the power relationships in the organisation and expect the outcomes to be different from what they are used to. As some in the organisation might experience sharing power as threatening, or be reluctant to deal with certain demands from the audience, it requires good leadership and capacity building among staff and artists. The organisation’s trust and support for the actively engaged audience – providing true freedom in programming and allowing them to make mistakes – will enhance the confidence and skills of the participants, which in turn will come to benefit the organisation.

Jancovich (2015) further maintains that short-term processes, for example, when participants are invited to co-curate an exhibition, are effective in building public value but not necessarily in influencing organisational change. Such processes are most transformative when embedded organisation-wide and allowed to run for the long term. Small project-based experiments could be developed within arts organisations to build the capacity and confidence of cultural leaders and managers in establishing such programmes. The sharing of power should also include other arts partners and partners from other sectors. As with collaborating artists and audiences, here too arts organisations should be aware of the power dynamics at play and avoid things like tokenism, being only symbolically inclusive of minority groups. Reich and Reich (2006) also point out that staff must become aware of informal hierarchies and disciplinary policies in the organisations as well as of their own biases and sensitivity to others.

Partnerships

Many scholars thus see collaboration as key to a sustainable audience development (e.g., Bollo et al., 2017; Cogman, 2013; European Commission, 2012; Fiaccarini et al. 2016). According to, e.g., Borwick (2012) and Brown and Ratzkin (2011), to build communities (rather than audiences), arts organisations should collaborate with partners across disciplines and sectors, as well as with, for instance, local businesses. In other words, partners ought to be seen as collaborators bringing in external, complementary expertise, not as competitors. Through partnerships, arts organisations gain access to new, and broader audiences. And, as we have seen, partnerships could remove social barriers to engagement, as the new audience is familiar with, and trusts the partnering organisation. Hayes and Slater (2002) add that partners better understand (have a holistic picture of) the target group’s behaviour, lives and interests. Interdisciplinary strategic partnerships and collaboration with other institutions either in the same sector or across sectors are likely to be an important feature in the future.

References

Arnett, D. B., S.D. German and S.D. Hunt. 2003. ‘The Identity Salience Model of Relationship Marketing Success: The Case of Nonprofit Marketing.’ Journal of Marketing, 67(2), 89–106.

Bamford, A., Wimmer, M. (2012). Audience Building and the Future Creative Europe Programme. European Expert Network on Culture [EENC short report].

Bollo, A., Da Milano, C., Gariboldi, A., & Torch, C. (2017). Audience Development. How to Place the Audience at the Centre of Cultural Organizations, Brussels: European Commission–Directorate-General for Education, Youth, Sport and Culture.

Boorsma, M. (2006). ‘A Strategic Logic for Arts Marketing.’ International Journal of Cultural Policy, 12(1), 73-92.

Borwick, D. 2012. Building Communities Not Audiences. Winston-Salem, NC: Arts Engaged.

Brown, A. S., & Ratzkin, R. (2011). Making Sense of Audience Engagement: A Critical Assessment of Efforts by Nonprofit Arts Organizations to Engage Audiences and Visitors in Deeper and More Impactful Arts Experiences. San Francisco: The San Francisco Foundation.

Brown, A. S. (2013). Engaging Next Generation Audiences: A Study of College Student Preferences towards Music and the Performing Arts. Hopkins Center for the Arts, Dartmouth College.

Bussell, H. & Forbes, D. (2007). ‘Volunteer Management in Arts Organisations: A Case Study and Managerial Implications.’ International Journal of Arts Management, 9(2) (WINTER 2007), 16-28.

Cogman, L. (2013). The Audience Development Toolkit. Retrieved from: http://www.culturehive.co.uk/resources/audience-development-toolkit/

Conner, L. (2013). Audience Engagement and the Role of Arts Talk in the Digital Era. London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Cravens, J. (2000). ‘Virtual Volunteering: Online Volunteers Providing Assistance to Human Service Agencies.’ Journal of Technology in Human Services, 17(2-3), 119-136.

Davies, M., & Wilkinson, H. (2011). Culture Change, Dynamism and Diversity. London: Museums Association.

De Voldere, I., & Zeqo, K. (2017). Crowdfunding. Reshaping the Crowd’s Engagement in Culture [Consultancy Report]. European Commission (EC).

European Commission (2012). European Audience: 2020 and Beyond. Conference Conclusions.

Fiaccarini, G., Gariboldi, A., & Righolt, N. (2016). Steps Towards a Good Audience Practice. Follow the Learnings of the ADESTE Project.

Foreman-Wernet, L., & Dervin, B. (2017). ‘Hidden Depths and Everyday Secrets: How Audience Sensemaking can Inform Arts Policy and Practice.’ The Journal of Arts Management, Law, and Society, 47(1), 47-63.

Hayes, D., & Slater, A. (2002). ‘”Rethinking the Missionary Position” – The Quest for Sustainable Audience Development Strategies.’ Managing Leisure, 7(1), 1-17.

Hotdoc (2015). Guidelines for Volunteer Management. Retrieved from:

http://assets.hotdocs.ca/doc/HD15_Volunteer_Management.pdf

Jancovich, L. (2015). ‘Breaking Down the Fourth Wall in Arts Management: The Implications of Engaging Users in Decision-Making.’ International Journal of Arts Management, 18(1), 14-28.

Kawashima, N. (2000). Beyond the Division of Attenders vs. Non-attenders: A Study into Audience Development in Policy and Practice. Centre for Cultural Policy Studies: University of Warwick.

Ellison, J. (2015). The Art of Partnering [Report]. London: King’s College London.

Landry, C. et al. (1996). The Art of Regeneration. Comedia: Stroud.

Lin, C., & Bruce, B. C. (2013). ‘Engaging Youth in Underserved Communities Through Digital-Mediated Arts Learning Experiences for Community Inquiry.’ Studies in Art Education, 54(4), 335-348.

Lipps, B. (ed.) (2015). Culture Shift: Creative Leadership for Audience-Centric Performing Arts Organisations. A Theatron Toolkit for Strategic Audience Development, Theatron.

Lowe, S.S. (2000). ‘Creating Community: Art for Community Development.’ Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 29 (3), 357-386.

Maitland, H., J. Meddick (2000). The Marketing Manual: For Performing Arts Organisations. Cambridge: Arts Marketing Association.

McCarthy, K., E. Ondaatje, L. Zakaras & A. Brooks (2004). Gifts of the Muse. Reframing the Debate About Benefits in the Arts. Santa Monica: Rand Corporation.

Nesta (2015). Digital Culture: How Arts and Cultural Organisations in England Use Technology. London: Nesta.

OMC (2012). A Report on Policies and Good Practices in the Public Arts and in Cultural Institutions to Promote Better Access to and Wider Participation in Culture. Brussels: Open Method of Coordination. Retrieved from:

http://ec.europa.eu/assets/eac/culture/policy/strategic-framework/documents/omc-report-access-to-culture_en.pdf

O’Sullivan, T. (2010). ‘Dangling Conversations: Web-Forum Use by a Symphony Orchestra’s Audience Members.’ Journal of Marketing Management, 26(7–8), 656-670.

Reich, S. M., & Reich, J. A. (2006). ‘Cultural Competence in Interdisciplinary Collaborations: A Method for Respecting Diversity in Research Partnerships.’ American Journal of Community Psychology, 38(1-2), 1-7.

Rentschler, R., J. Radbourne, R. Carr and J. Rickard. 2002. ‘Relationship Marketing, Audience Retention and Performing Arts Organisation Viability.’ International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing, 7(2), 118–130.

Sidford, H., Frasz, A., Hinand, M. (2014). Making Meaningful Connections: Characteristics of Arts Groups that Engage New and Diverse Participants. James Irvine Foundation.

Stallings, S. & B. Maudlin (2016). Public Engagement in the Arts. A Review of the Literature. Los Angeles: Ford Theatre Foundation & Los Angeles Arts Commission.

Stamer, D., Lerdall, K., & Guo, C. (2008). ‘Managing Heritage Volunteers: An Exploratory Study of Volunteer Programmes in Art Museums Worldwide.’ Journal of Heritage Tourism, 3(3), 203-214.

Stern, M. J., & Seifert, S. C. (2013) Cultural Ecology, Neighborhood Vitality, and Social Wellbeing – A Philadelphia Project. Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania/Social Impact of the Arts Project (SIAP).

Scitovsky, T. (1976), The joyless economy. London: Oxford University Press.

Trienekens, S. (2018), Ontmoet MusicGenerations & Talent voor Gastvrijheid. Amsterdam: UrbanParadoxes.

Trienekens, S. (2019a), Duurzaam investeren in nieuwe makers. Evaluatie regeling Fonds Podiumkunsten. Amsterdam: UrbanParadoxes.

Trienekens, S. (2019b) Forthcoming in W. Modest (ed.). ‘Doing Diversity’. Amsterdam: Nationaal Museum van Wereldculturen.

Vlieghe, J., Muls, J., & Rutten, K. (2016). ‘Everybody Reads: Reader Engagement with Literature in Social Media Environments.’ Poetics, 54, 25–37.

Walmsley, B. & Franks, A. (2011). The Audience Experience: Changing Roles And Relationships. Author produced version retrieved from: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/79377/

Walmsley, B. (2013). Co-creating Theatre: Authentic Engagement or Inter-Legitimation? Cultural Trends, 22(2), 108–118.

Walmsley, B. (2016). ‘From Arts Marketing to Audience Enrichment: How Digital Engagement Can Deepen and Democratize Artistic Exchange with Audiences.’ Poetics, 58, 66-78.

Webster, Mark & Ben Buglass (2005) Finding Voices, Making Choices. Creativity for Social Change. Nottingham: Educational Heretics Press.